Team Dynamics

Must post first.

View “Remember the Titans – Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing, Adjourning,” a YouTube video hosted by kpkammer.

Describe any team dysfunction and/or effective team characteristics you saw in the video.

• How do the scenes in the video illustrate the different stages of team development?

14.6aStages of Team Development

After a team has been created, it develops by passing through distinct stages. New teams are different from mature teams. Recall a time when you were a member of a new team, such as a fraternity or sorority pledge class, a committee, or a small team formed to do a class assignment. Over time, the team changed. In the beginning, team members had to get to know one another, establish roles and norms, divide the labor, and clarify the team’s task. In this way, each member became part of a smoothly operating team. The challenge for leaders is to understand the stages of development and take action that will lead to smooth functioning.

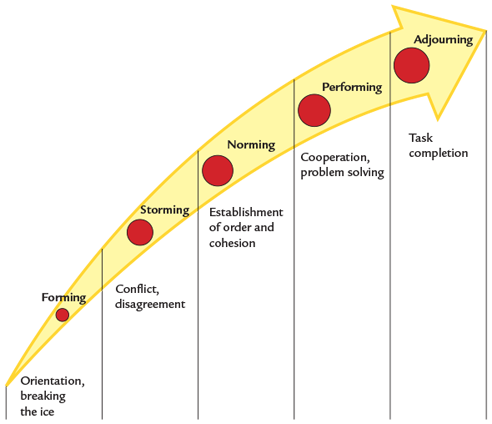

Research findings suggest that team development is not random, but evolves over definitive stages. One useful model for describing these stages is shown in Exhibit 14.7. Each stage confronts team leaders and members with unique problems and challenges.

Exhibit 14.7Five Stages of Team Development

SOURCES: Based on the stages of small group development in Bruce W. Tuckman, “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups,” Psychological Bulletin 63 (1965): 384–399; and B. W. Tuckman and M. A. Jensen, “Stages of Small Group Development Revisited,” Group and Organizational Studies 2 (1977): 419–427.

FORMING

The forming stage of development is a period of orientation and getting acquainted. Members break the ice and test one another for friendship possibilities and task orientation. Uncertainty is high during this stage, and members usually accept whatever power or authority is offered by either formal or informal leaders. During this initial stage, members are concerned about things such as “What is expected of me?” “What behavior is acceptable?” and “Will I fit in?” During the forming stage, the team leader should provide time for members to get acquainted with one another and encourage them to engage in informal social discussions.

STORMING

During the storming stage, individual personalities emerge. People become more assertive in clarifying their roles and what is expected of them. This stage is marked by conflict and disagreement. People may disagree over their perceptions of the team’s goals or how to achieve them. Members may jockey for position, and coalitions or subgroups based on common interests may form. Unless teams can successfully move beyond this stage, they may get bogged down and never achieve high performance. A recent experiment with student teams confirms the idea that teams that get stuck in the storming stage perform significantly less well than teams that progress to future stages of development.

NORMING

During the norming stage, conflict is resolved and team harmony and unity emerge. Consensus develops on who has the power, who the leaders are, and what the various members’ roles are. Members come to accept and understand one another. Differences are resolved, and members develop a sense of team cohesion. During the norming stage, the team leader should emphasize unity within the team and help to clarify team norms and values. Creating a new way of operating a theater company, along with new norms, was Eric Tucker’s goal, when he started Bedlam Theatre Company with Andrus Nichols, as shown below in this chapter’s Executive Edge.

The Executive Edge

BEDLAM THEATRE COMPANY

To have The Wall Street Journal say your theater company is “one of the most innovative troupes at work today,” and that you are “high on the list of America’s most engaging and imaginative stage directors” is no small feat. Yet in less than three seasons, artistic director Eric Tucker’s Bedlam Theatre Company has sprinted from zero to 30 miles per hour without breaking a sweat.

Getting that kind of success so quickly requires keen artistic abilities, but it also needs competent management skills. After all, it’s called show business for a reason. As sought-after director and actor, Eric Tucker got tired of being on the road constantly, so he decided to create his own New York–based theatre company that would have the kind of artistic vision and take the sorts of risks he was after. And he had enough smarts to know he needed someone who could handle most of the business side. Because, at the end of the day, he says, “When you start a theatre company, you’re starting a business.” And you must be prepared to run a business until you do well enough to hire someone to take over those tasks. But in the beginning, he and his business partner Andrus Nichols, one of the company’s central actors, did everything themselves—from payroll to insurance to printing playbills to finding costumes to negotiating with the actor’s union.

Tucker knew from the start he had to treat people well, because he knew the importance of creating a high-performing team. He’s developed a troupe of people he works with over and over again, because they get to know each other, and there is a kind of communication “short-cut” that occurs. When they start working on a new play, Tucker does not have them do the “normal” sitting around a table and reading the script. Instead he has them “play” around with various roles in that play, mostly with improv, so that he gets to know the strengths and weaknesses of each actor and then can build the play around what he has. “It’s difficult when a director has an idea that does not match the cast,” he says from experience, and he likes to leave time for the actors to feel they have creative freedom in what is being created, so that they have a “safe” place to experiment without being judged. He’s found this leads to actor engagement, trust, and high performance.

Working as a team is not only for the artistic side, but also the organizational. People who start theatre companies often don’t know this, he says, but you never stop fund-raising. That means constant interaction with people, developing bonds and alliances, working toward common goals—all things teams do. “Your whole life is about finding money and asking people for money.” And because of his good team skills, Bedlam makes resourceful use of that money.

SOURCES: Eric Tucker, Personal communication, April 2015; Terry Teachout, Two Stagings, ‘Twelfth Night,’ Wall Street Journal Online, April 3, 2015 (accessed April 14, 2015), http://search.proquest.

PERFORMING

During the performing stage, the major emphasis is on problem solving and accomplishing the assigned task. Members are committed to the team’s mission. They are coordinated with one another and handle disagreements in a mature way. They confront and resolve problems in the interest of task accomplishment. They interact frequently and direct their discussions and influence toward achieving team goals. During this stage, the leader should concentrate on managing high task performance. Both socioemotional and task specialist roles contribute to the team’s functioning.

ADJOURNING

The adjourning stage occurs in committees and teams that have a limited task to perform and are disbanded afterward. During this stage, the emphasis is on wrapping up and gearing down. Task performance is no longer a top priority. Members may feel heightened emotionality, strong cohesiveness, and depression or regret over the team’s disbanding. At this point, the leader may wish to signify the team’s disbanding with a ritual or ceremony, perhaps giving out plaques and awards to members to signify closure and completeness.

Spotlight on Skills

MCDEVITT STREET BOVIS

Rather than the typical construction project characterized by conflicts, frantic scheduling, and poor communication, McDevitt Street Bovis wants its collection of contractors, designers, suppliers, and other partners to function as a true team, putting the success of the project ahead of their own individual interests.

The team-building process at Bovis is designed to take teams to the performing stage as quickly as possible by giving everyone an opportunity to get to know one another, explore the ground rules, and clarify roles, responsibilities, and expectations. The team is first divided into separate groups that may have competing objectives—such as the clients in one group, suppliers in another, engineers and architects in a third, and so forth—and asked to come up with a list of their goals for the project. Although interests sometimes vary widely in purely accounting terms, common themes almost always emerge. By talking about conflicting goals and interests, as well as what all the groups share, facilitators help the team gradually come together around a common purpose and begin to develop shared values that will guide the project. After jointly writing a mission statement for the team, each party says what it expects from the others, so that roles and responsibilities can be clarified. The intensive team-building session helps take members quickly through the forming and storming stages of development. “We prevent conflicts from happening,” says facilitator Monica Bennett. Leaders at McDevitt Street Bovis believe that building better teams builds better buildings.

These five stages typically occur in sequence, but in teams that are under time pressure, they may occur quite rapidly. The stages may also be accelerated for virtual teams. For example, at McDevitt Street Bovis, a large construction management firm, bringing people together for a couple of days of team building helps teams move rapidly through the forming and storming stages.

Thank you

Solution Preview for Team Dynamics

APA

309 Words